Visiting Illycaffe, Trieste

In December I made a short visit to Trieste, Italy, where I was invited to give a seminar at the Trieste Observatory. Fantastic hospitality! I ate extremely well and was excellently looked after. Here’s a short account of what happened….

For espresso drinkers, Trieste is indelibly associated with the name of Illy. It was in Trieste that Illy created the first espresso machine, the Iletta, and Illy coffee beans is the only Italian espresso of high quality that is available throughout the world, thanks to the Illy method of packing the coffee beans with a neutral atmosphere under pressure. So I was amazed to discover, a few months previously, that the brother of my host was highly placed in the Illy coffee hierarchy and a seminar in Trieste seemed an ideal occasion to arrange for a visit to the Illy factory.

After my arrival, and an excellent meal near the observatory, at 3pm we drove to the Illy factory near the Trieste docks. It’s there, for almost a hundred years, that green beans have arrived from remote corners of the world to Illy’s factory. Crossing the port of Trieste we could see in the middle distance, on the hillside, a very tall chimney. This, I was told, was the chimney of the Illy coffee factory. The chimney is of such a great height so that only the freshest possible air is used in the roasting process; it’s actually an air intake, rather than an exhaust.

At Illy we were outfitted with visitor tags and of course the tour started with an excellent espresso! At the centre of the reception area is a gleaming bar where free cups of excellent espresso are served to anyone who asks. Here, where espresso was invented, one might regard this cup as the definitive version. I took an espresso with my friends and we talked to the bartender. It was indeed an excellent espresso; I realised now to what level I have to strive each afternoon at the IAP when I prepare espresso for my friends.

Our tour of the factory lasted over two hours, in the main part because myself and my colleagues were very inquisitive. Our tour started with the coffee bean selection process. We were led into a narrow glass-fronted room which overlooked what I can only describe as a waterfall of green coffee beans, a vast avalanche of coffee grains. Here the crucial selection process took place: the reflected light from each coffee bean is carefully examined and if it does not fall within a carefully pre-determined spectrum pffttt! it is ejected with a blast of compressed air. A few other coffee beans are naturally taken out with it but no matter: one bad coffee bean, we are told, is enough to spoil an entire cup of espresso.

After selection, the coffee beans are roasted and then travel in pipes propelled by compressed air to the packaging plant. Walking over there I stood amidst countless machines that relentlessly filled one coffee tin after another with Illy coffee beans and then carefully pressurised the tin with neutral gases. I realised that every single tin of Illy coffee in the entire world came from this factory: there is no other production facility. Illy also make their own tins, which are tested to make sure they don’t explode under pressure an automated process which which we witnessed (and were I nervously awaited an extremely large bang.) Throughout the shop floor I saw espresso machine after espresso machine: at each stage of the packaging process espresso coffee is regularly brewed and tasted (how do these people sleep at night?) to make sure that only the highest-quality product is shipped.

The most wondrous place, however, was the Illy coffee laboratory. Here it was explained to us how Illy selects the coffee beans which will be used in their espresso blend. When a sample of coffee beans arrive at the factory, they are first examined under the microscope, to make certain they have the correct colour and shape. Okay. But the next step I found quite amazing. Illy scientists make measurements of each coffee bean using a near-infrared spectrometer. Our guide pulled out a thick binder showing the results of such tests. I was amazed. These plots were what I as an astronomer would recognise as a colour-colour diagram; each axis shows the difference between two adjacent spectral filters. If an astronomer wants to find a distant galaxy, he looks for objects which fall into a particular region of colour-colour space. Galaxies at redshift of around three are here, lower-redshift galaxies are there. But at Illy, they carried out exactly the same experiment! Good coffee beans lurked in this region of colour-colour space, bad coffee beans in this one! I had always suspected that astronomy and espresso were intimately connected, but now I had proof.

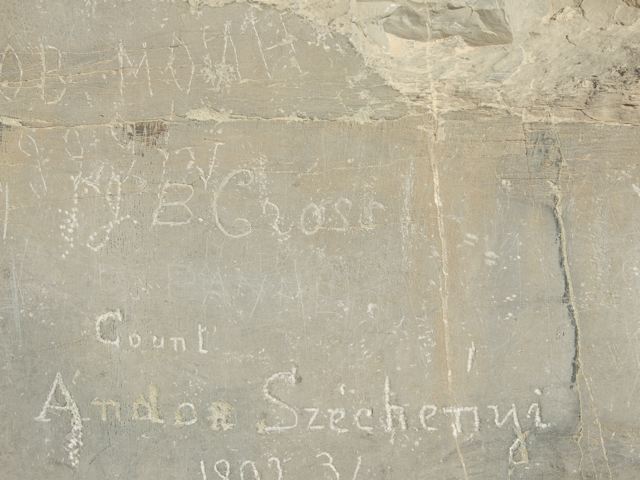

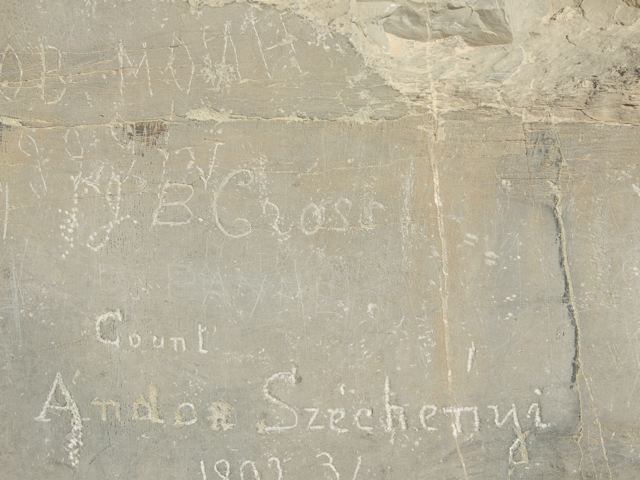

We left the factory and returned to the observatory just as the winter light was fading. I worked for further hour or two at the observatory before leaving to eat an evening meal with my colleagues. The next morning, climbing up the hillside to the observatory before my talk, I made an interesting discovery…. I knew that Jimmy Joyce had lived in Trieste but I had not realised it was so close to the observatory…and, wasn’t that someone’s washing hanging out just next door?

I remembered Flan O’Brien’s hilarious Dalkey Archive, in which James Joyce has a double career stitching Jesuit underwear…