Auster and Descartes: reading 4321

Paul Auster’s work has a certain resonance for me. I first discovered his books in that distant summer of 1991 when I made my first trip to America. In fact, I bought “In the country of last things” at the famous Strand bookshop in Manhattan. I read it on my ten-day greyhound bus journey to Socorro, New Mexico where I spent a long six months as a “summer intern” (finishing in December!) at New Mexico Tech. It was a strange and mysterious experience to read that book about the end of the world as the countryside unrolled around me back to zero and dissolved into desert. In the next six months out there I discovered Moon Palace and the New York Trilogy. It seems strange now because the first places and last places I saw on this trip to America was Manhattan, the deserts of New Mexico, and finally San Francisco, and all of those places play a central role Auster’s early novels.

By the time I had arrived in the deserts of New Mexico it was hard enough for me tell the difference between what happens inside books and what happens outside them. Here’s an example: in one scene in Moon Palace the central character is instructed to take a trip to a Brooklyn art gallery, keeping his eyes closed, and only open then when he arrives before a certain painting — “Indian by moonlight”. I had of course never heard of this painting but I was curious, what did it look like? In the middle of my stay in New Mexico I made a trip back to New York and I knew I wanted to visit that Brooklyn Gallery and see the painting. I phoned the gallery. Do you have a painting called “Indian by Moonlight” in your collection, I asked them. Yes, they said. Could I see it? Well — no. You see, they explained to me, it’s in a part of the gallery where there are no lights. We could take you down there, but you couldn’t see it. So, even if I opened my eyes, I couldn’t see the painting.

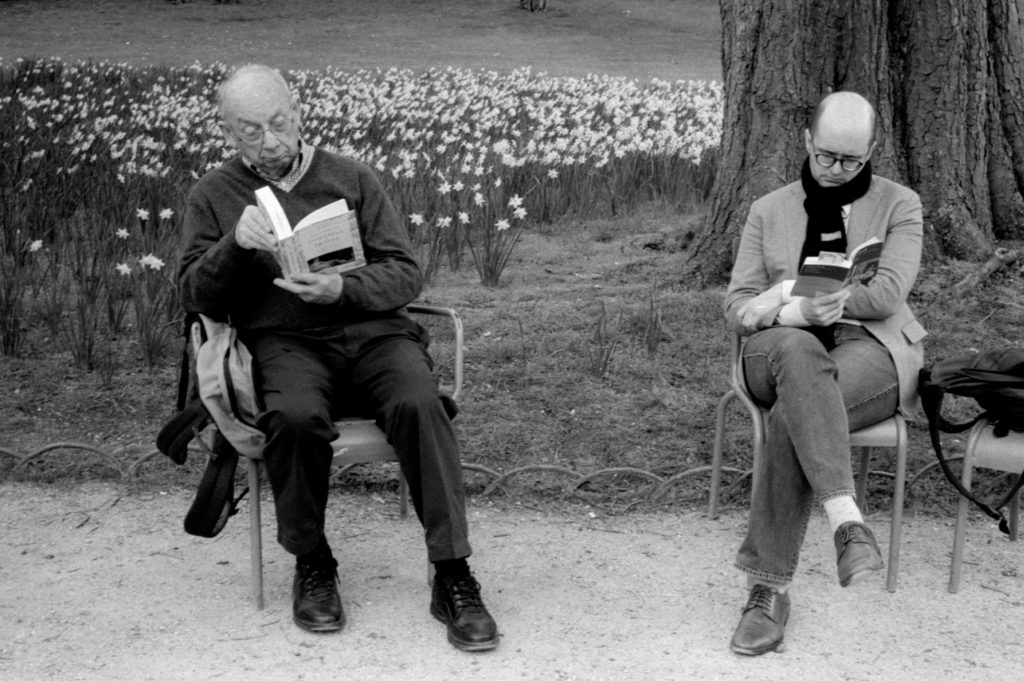

Well, as they say — years passed. And now I find myself living in Paris. A few months ago in our local bookshop I chanced on an enormous tome, 4321 it said, and it was by Mr. Paul Auster. It had been years since I had read any novel by Paul Auster. I hesitantly picked it up. I wasn’t frightened of big books, but yes maybe I have less time now, so I didn’t buy it just then. But I was curious. A few weeks later when I learned I had to make a trip back to the Salpé hospital, I knew that afterwards I’d have enough time to read it. And so I did, all one thousand words in around a week, comfortably installed on the couch in the front room.

Perhaps you’ve heard the central conceit of the book: Mr. Auster imagines three other versions of approximately his own life. Four stories in total. Only, the other three lives are cruelly cut short: the other Paul Austers do not make it to the end of the book. One is struck dead in his youth, more or less, by a bolt of lightning, an event which Auster himself narrowly avoided. That must have been hard for Auster to write especially because their deaths seem at times arbitrary and capricious. So, the book is a reflection on the different paths that lead to a life. Starting with the same raw material, the same inklings and desires, talents and failings, what would we become? Each Auster makes slightly different choices, meets different people, becomes a different person.

Paris (a city, one character says, I have never heard anyone say bad things about) lies near the heart of the story. There are the familiar tropes about writing books and creating works of art in that glittering city and Auster manages mostly to stay away from cliche. The history of America after the war is finely detailed and it struck me just how turbulent and unsettled those times were. Assassination of one public figure followed another, JFK and MLK and RFK. We think that our times are difficult now!

Auster paints on a very broad canvas but despite the sweep of history this is not Dellilo’s Underworld. At first, seeing the size of the book, I wondered, would this be Auster’s big book, the career-defining masterpiece? In the end, I am not so sure. If there had only been one of the four stories in the book, would it have been as interesting? Are any of the stories interesting in and of themselves? Although, really, the fascinating aspect here is just how each of the four stories interrelate to each other. The different Austers swelter in impossibly hot New York summers or travel to Paris for a week or a month or for years. His mother becomes a famous photographer or is a portrait photographer for families and weddings or closes her studio and abandons her art. Reading the book, one cannot help wondering what are the inflection points in one’s own life that might have a led to a different outcome. We have each have innate talents and gifts, how are they expressed differently?

Finally, there is only one thread and there is only one writer. We are in Rue Descartes, Paris. This, we are told, is where the book was finished. Auster must surely know Milosz’ poem Bypassing rue Descartes. Rational systems destroyed the cities of Europe and killed millions. Weighted against that, to protect us, tradition and custom. For Auster, I suppose, on one side is our innate nature, on the other, our environment. It is impossible to know all these alternate lives that we may have led. This book, at least, makes us think about them.