(This is the second part of a two-part article. Read the first part here).

Now skip ahead once again another ten or fifteen years. I found this fascinating book “The great star chart” written by a British astronomer, H.H. Turner, about the progress of the “Carte de Ciel” survey. Turner was an astronomer at the University of Oxford, and this short book is his account of the survey and the work that had been accomplished in Oxford by 1911.

It’s interesting to consider his book from a modern perspective: in those distant days our notions of the Universe were very different; cosmology did not exist as a science, Einstein had yet to formulate his theory of General Relativity, and we didn’t know what the true nature of the nebulae — those dim smudges which were picked up on the photographic plates from time to time — really were. That meant interpreting observations on the first deep plates quite challenging. In Turner’s book there is a lot of talk about the “fog” that might exist between the stars — that this fog might be part of an explanation why the numbers of stars varies so much from plate to plate. Were clusters of stars and were there really “stellar streams”? Similar confusion would exist in the coming years when we tried to understand the distribution of the counts of “nebulae” on the plates — was this variation again because of some kind of “fog” or was the distribution of the galaxies really non-uniform?

It turns out, that like a lot of things, the answer was a bit of both: there really is dust, but the distribution of stars and galaxies on the sky really is clustered, for the former because of the shape of our own milky way galaxy, and the latter because … well, that’s a much longer story. But it’s interesting to think of the parallels between counting stars to find out about the Milky Way and counting galaxies to find out about the Universe.

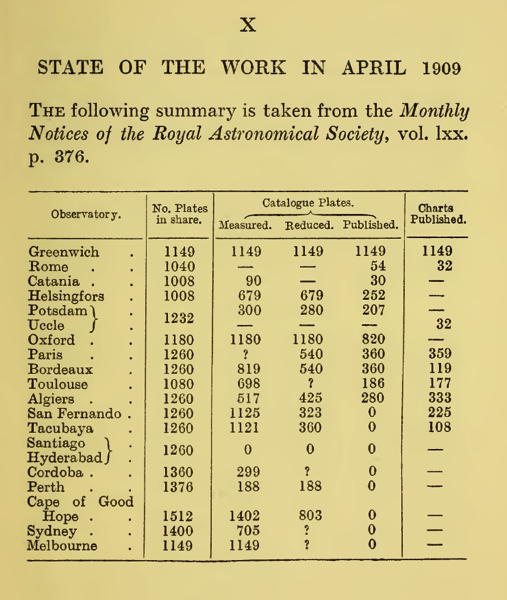

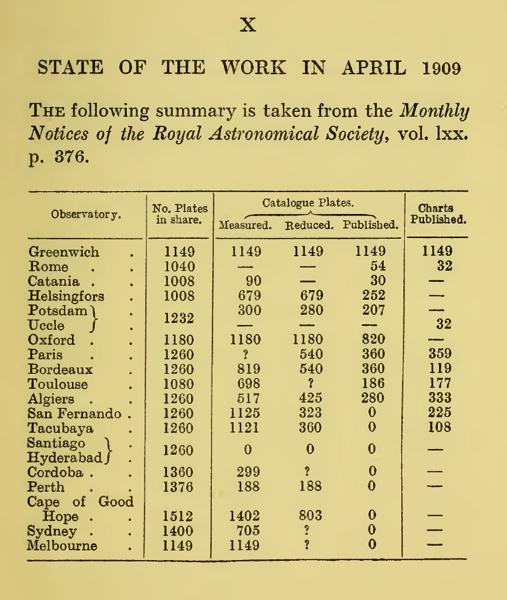

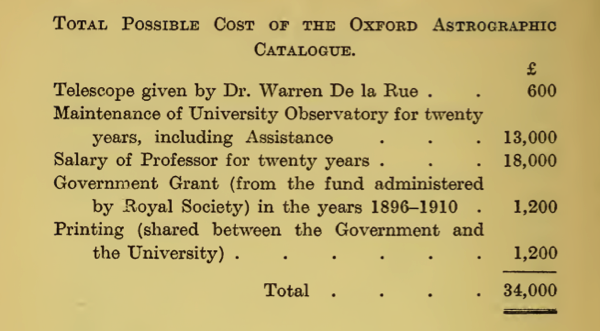

But getting back to the “carte du ciel”… There is the interesting table I have reproduced below, which shows the state of survey after ten years of operations, divided by into catalogue plates (the shallower survey) and “charts published” which are reproductions of the deeper survey plates.

Here it is:

|

| Who actually got some work done |

While some progress has been made in measurement, it is already clear at this stage that printing the plates will be very expensive: based on the techniques used in Paris to reproduce their part of the survey, Turner calculates that a complete set would weight over four tonnes, if it were ever to be completed. Printing the entire set would be staggeringly expensive.

The work was very time-consuming: it had taken four or five astronomers working full time almost ten years in Oxford to complete their part of the survey. The work was mind-numbingly repetitive, involving countless calculations to produce a catalogue for a single plate. Every position of every one of the stars on the plate was measured manually. To guard against errors, the plates were rotated 180 degrees and the measurement made a second time, and the positions compared. In those days “computers” were in fact room-full of workers with slide-rules. In fact, this chronic mismatch between the data-gathering capabilities of telescopes equipped with photographic plates and our ability to process it would last until the 1960s when digital computers finally became fast enough to handle the volumes of data involved. (In fact, the first extragalactic surveys also suffered from a lack of computing power, but that is a story for another day.) Given all this, it’s hardly surprising that very few observatories, more than ten years after the survey started, had completed their quota of plates. It’s interesting to note in passing that it is also said in some quarters the reason why Europe lagged America in the new science of observational cosmology was because all the astronomers on this side of the pond were tied up measuring positions of stars on thousands of photographic plates.

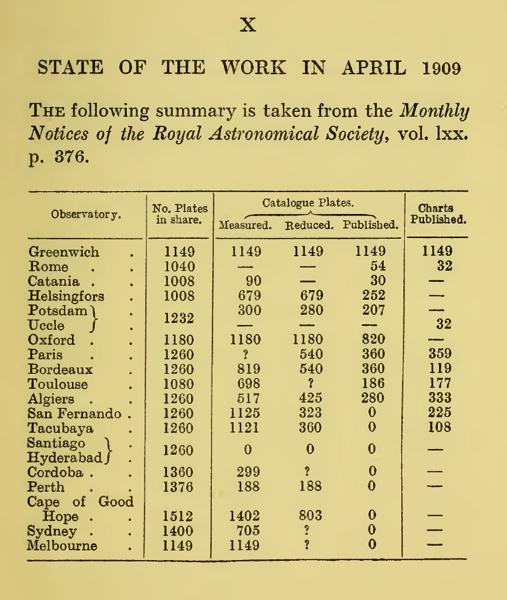

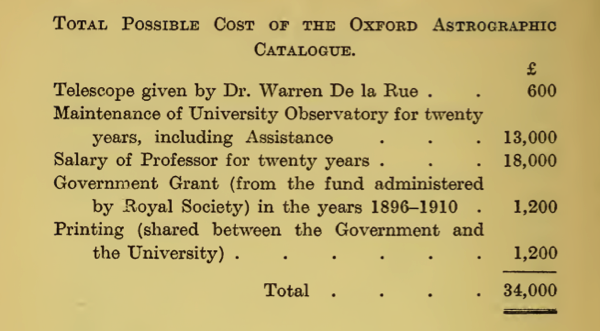

Turner also talks about cost.

|

| And how much it cost… |

Well, not much has changed in survey operations in the last century or so: today staff costs and maintenance remains the most expensive items in running a survey. What is interesting from a contemporary point of view is that Turner talks about the trade-off between accuracy and speed: it’s obvious that in an undertaking this size, attempting to make the measurements to infinite precision would simply take infinitely long. Better do the job well enough to get the necessary precision — but not too well, otherwise it will never get finished. Tell that to a student finishing their first paper.

How could other observatories with smaller amounts of staff hope to complete such a massive enterprise? In fact, they couldn’t. The deeper survey plates were never printed out — it was simply too expensive. The rest of the survey, the astrographic catalogue, did actually get finished sometime in the 1950s, almost half a century after it started. In the 1980s and 90s, with the arrival of cheap and fast computing power, interest in the survey returned. One group of astronomers recalculated all the positions of the stars in the astrographic catalogue and compared them to those taken a century later with the Hipparcos satellite.

Another group turned to the photographic plates. Although plate-scanning equipment had been around for a while, it was much too slow to scan the plates of the survey, machines like the PdS microdensitometer would take one day to scan a single plate. Instead, another group of astronomers used off-the-shelf photographic film scanners to digitize some of the plates (this was in the last ten years) and compare them to more recent catalogues. In both cases, the age of the old plates becomes their greatest asset, providing an enormous baseline to measure the motions of stars in our galaxy…

Today, the carte du ciel is one of the major attractions at the “journee du Patrimoine” at the observatory. In fact, here you can see interested members of the public waiting to visit the old rusting domes of the carte du ciel this year just to hear this story that I’ve been telling you…

|

| The public visits the “carte du ciel”! |

We are just getting started. The Gaia satellite will be launched in the next month or so and will provide the most precise measurements of untold numbers of stars in the Milky Way. Euclid, further down the line, will do the same thing for galaxies. But we had better make sure the astronomers are properly motivated and that there are enough resources in place to complete the project, and actually do science with the data !