Descending beneath Paris: second part, at minus 25

The first impressions deep underground are always the same: it’s damp, cold and dark. Wellington boots are an essential element of clothing. The tunnels are very close to the level of the water table, and flooding is frequent. In certain tunnels the water level can easily reach waist level, although thankfully we avoided those. The water is a silty white colour, full of limestone dust.

But passing through the hole, further into the tunnel, you should pause and look around: the surface of the walls are smooth and well-preserved. Here, we were at almost the southern limit of this particular segment of the network, and we would have several kilometers to march before we got to where we wanted to be — near Denfert Rochereau, underneath my house, near the Observatory.

The underground passageways for the most part follow faithfully the above-ground streets, as a consequence of an arcane part of French law: anyone who owns a bit of land on the surface also owns what is below. So no boring tunnels under other people’s houses: the tunnels would have to be where the streets already were. At times, this leads to some strange effects, as the tunnels in places were constructed hundreds of years ago and were given the names of above-ground streets which no longer exist, or which do exist but which changed their names.

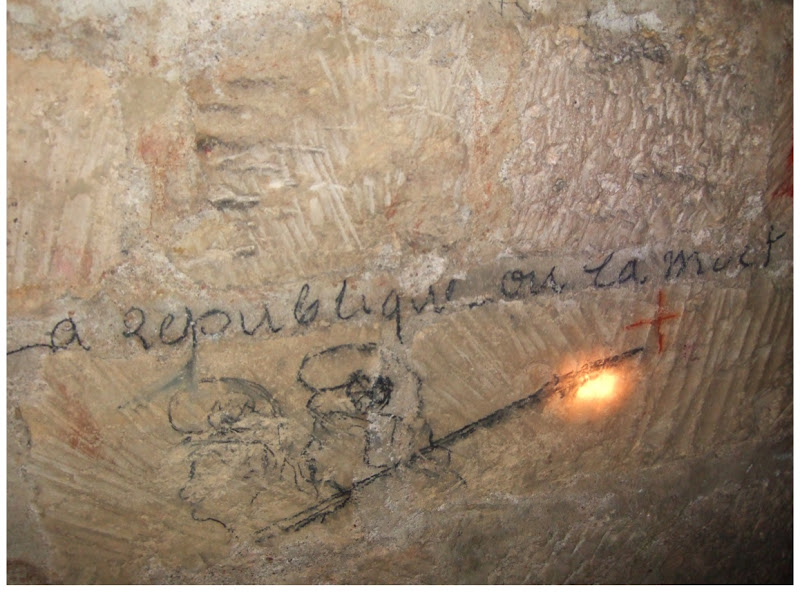

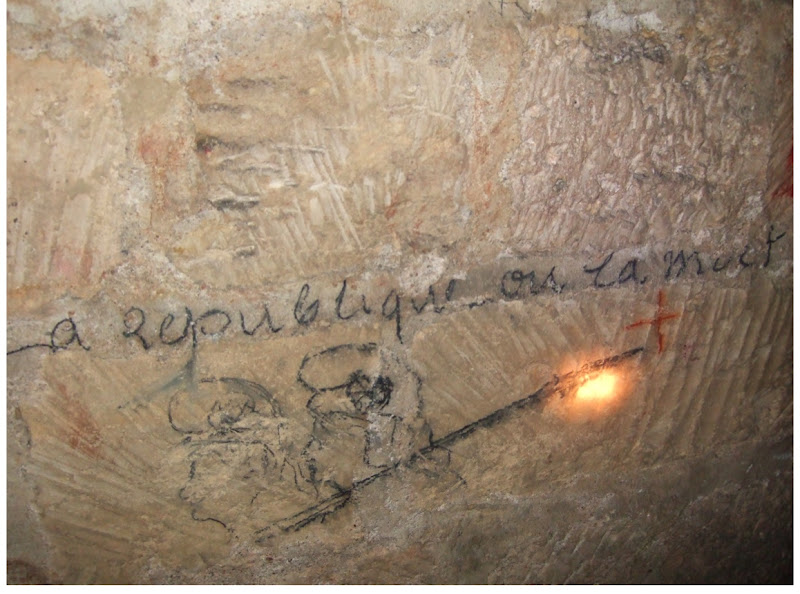

We followed one such street, the Avenue D’Orlean, which is now the Avenue du General le Clerc at street level. Walking down the narrow tunnel of course I kept my eyes to the ground but my friend leading us was inspecting carefully every inch of tunnel and ceiling. He showed me an inscription on the wall, some ancient graffiti — someone had scrawled “la republique ou la mort” — ancient revolutionary graffiti dating back a century or two. Above ground, everything changes, but down here at minus twenty five metres below, all is frozen preserved, perhaps like astronaut footsteps on the surface of the moon.

We made a tour of a few of the more well known sites in the 14th — old rooms packed to the ceiling with ancient human bones, student wall murals dating back a few decades, plaques proudly announcing to a public that hasn’t been down here for a century or more the names of the engineers who built the walls and tunnels and pillars absolutely essential to keep the new Paris metro disappearing into a large hole. For almost any construction work to be carried out in Paris one of the first things one must do is find out just what is exactly beneath your feet, and build down there, too.

We emerged into the fading evening light after spending around eight hours underground. It is always strange be once more in a world with light and colour where there are trees which move in soft summer breezes and one can hear the distant sounds of the city, birds singing, people talking, cars in the street. All so different from the silent, dark, frozen parallel Paris which we left behind but which remains very close…