Josef Koudelka: “La fabrique d’Exils” (Centre Pompidou, Feb 22-May 22nd 2017)

Koudelka is the last. In an interview with a the journalist Sean O’Hagan in 2008 he tells this story “‘Once, Henri [Cartier-Bresson] rang me in Paris and said, “Josef, Kertész is in town, you must come to dinner and meet him.” He held Kertész in the highest regard as a photographic master. I said, “Henri, I love his pictures but I do not need to meet him.” The phone goes down. Then he rings back and says, “No, you do not understand, you have to meet him because we three, we are of the same family.” At the time, this seems to me to be an unbelievable thing to say. Now, though, when I look back from a distance, I can see that maybe there is something in that.’

Each of these three photographers made their own unique and vital contribution to photography. Although the oldest, Kertsesz was the most modern (Koudelka’s words). Cartier-Bresson was of course the master of lightly ironic, perfect compositions and “photoportraits”. He managed to be invisibly present at many of the defining moments of twentieth century history, taking pictures of those who were there and not the thing that was happening. Koudelka, like Kertész, was a rootless exile with an approximate command of language. But unlike Kertész, he never did a job he didn’t want to do. And Koudelka is the last of these three still alive.

We are fascinated by creation and the artistic act. We always wonder how the sculptor reveals the head buried in the block of marble. We want to know what the trick is, how it’s done. What’s behind the curtain. Here in Paris, Josef Koudelka recently gave a selection of prints to the Centre Pompidou (Beaubourg). These works form the basis of a new exhibition, “le fabrique des exiles”, which runs until May. Yes, it is in some senses a “making of” of one of the great photography books of the 20th century, “Exiles”. The book is accompanied by a essay by Koudelka’s friend and collaborator of 40 years, Michel Frizot, which follows closely the path that Koudelka took to create his work.

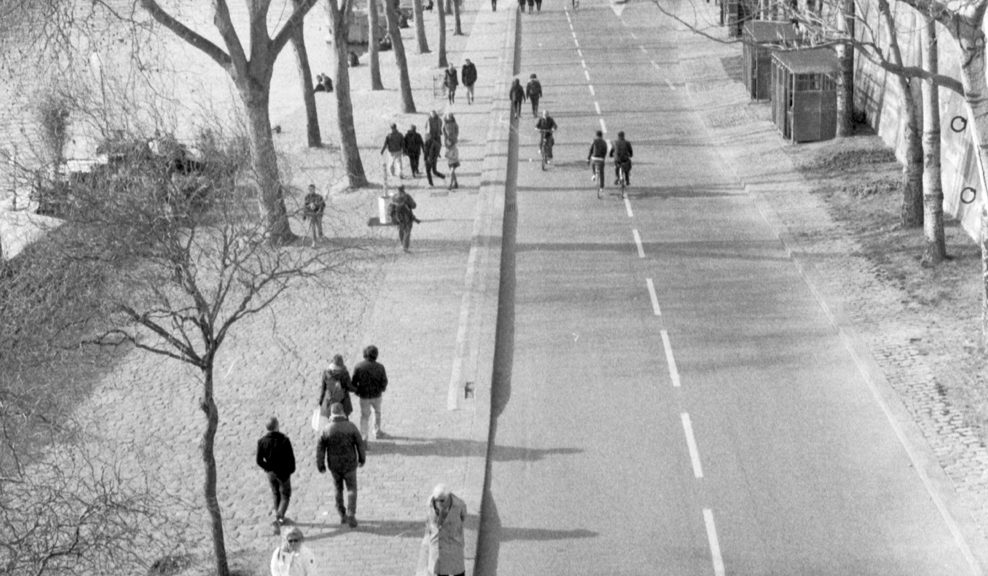

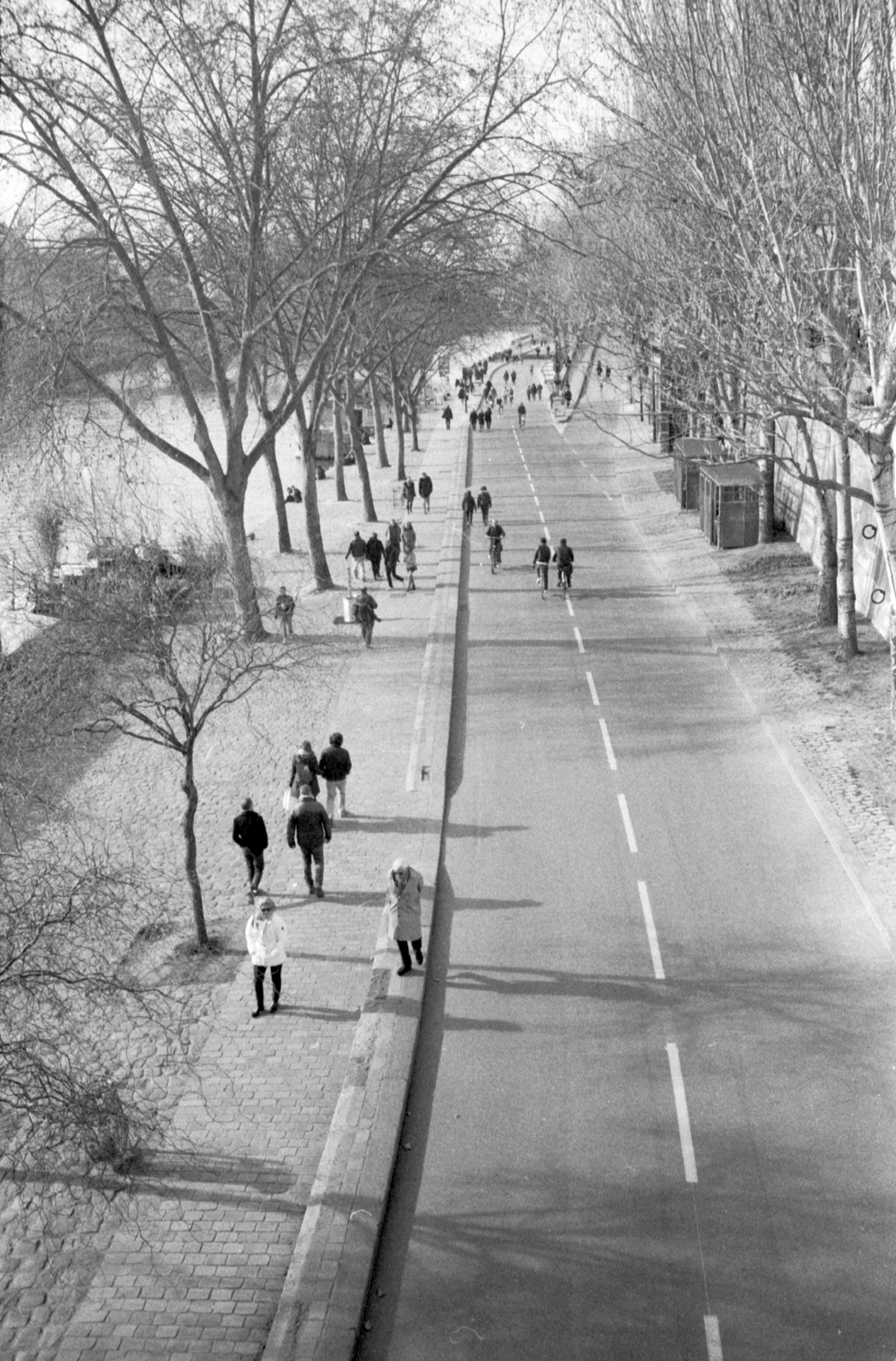

“Exiles” comprises around a hundred black-and-white photographs taken mostly in the 1970s and 80s. Certain have carved a place for themselves in our collective photographic consciousness as deep as any other works from the 20th century. Many of them have a certain strangeness or melancholy; others are graphic and expressionist. Seeing large prints of these photographs in Beaubourg amplifies their power. The grain becomes razor sharp, the blacks become inky black. There is that lost dog silhouetted in a wasteland of grimy winter snow at the Parc de Sceaux or outline of a man with an umbrella and flowers against the graceful curves of a wall somewhere in Europe.

The broad details of Koudelka’s life are well known. The publication of his pictures of Russian tanks rolling into Prague in the spring of 1968 made “P. P. – Prague photographer” an international celebrity — and especially someone highly sought after by the communist authorities in his native Czechoslovakia. Soon enough, there would be a trip abroad from which he would not return, transforming him too into a perpetual exile. He would spend the next decades photographing at festivals and country fairs in a half-dozen different European countries.

He was not interested in the events themselves but rather what was happening at the periphery, the edges. Before and after. He was not an anthropologist, and this work was not reportage.

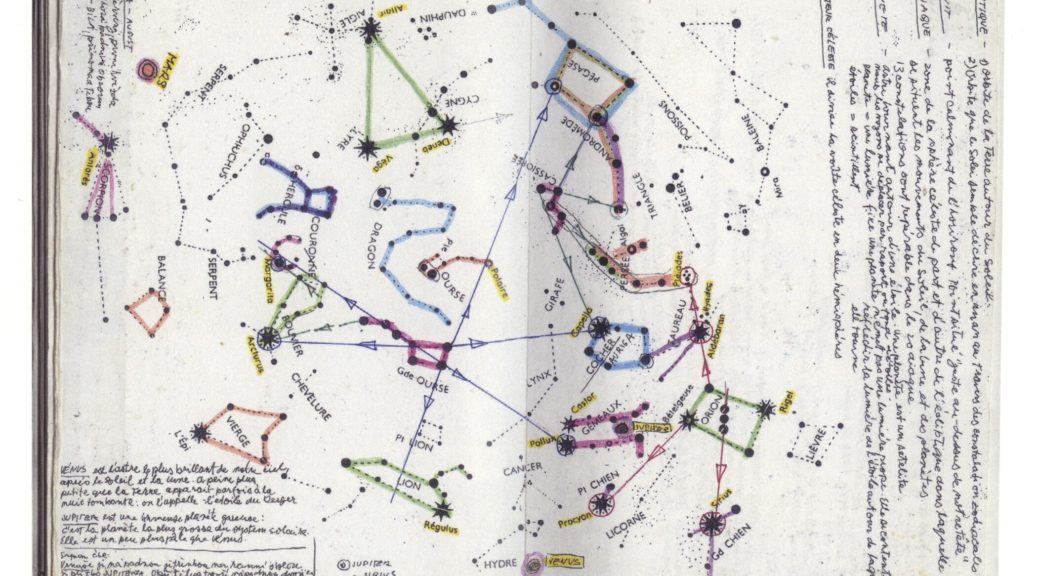

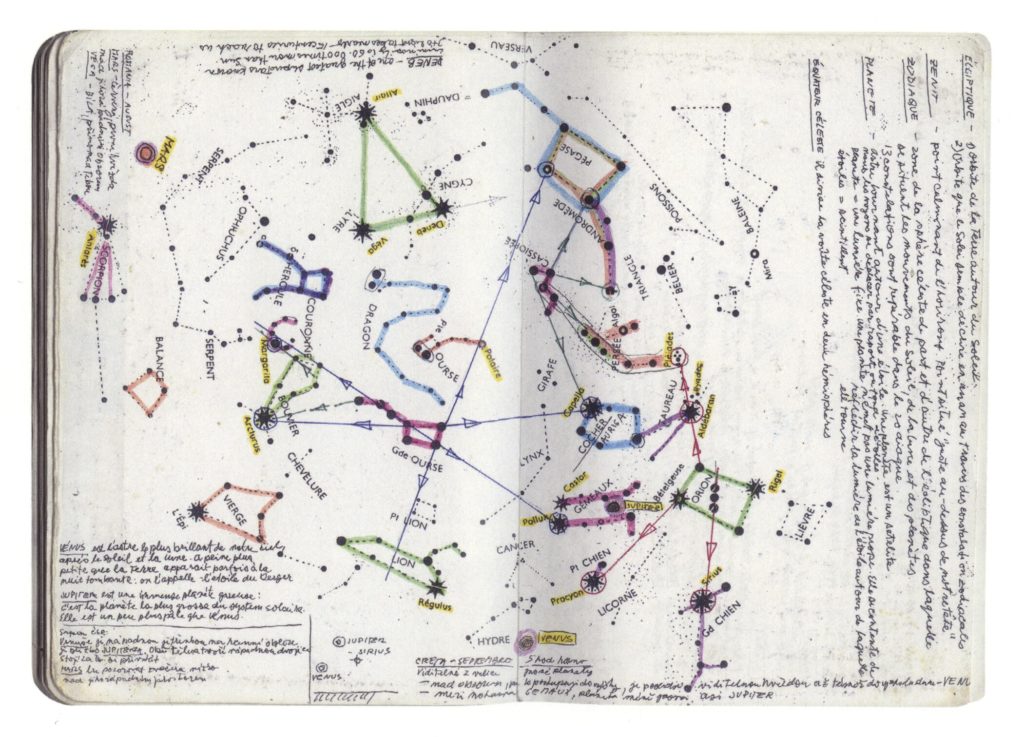

Frizot reveals Koudelka’s notebooks. Trained as an engineer, Josef K. planned his journeys with meticulous precision, and one can see these detailed agendas. But there are also other wonders, such as the chart of constellations together with details on the stars and planets. A useful thing to have if you need to get somewhere.

He traveled with almost no possessions and made no place his home, sleeping outside in the spring and summer and in the Paris Magnum offices or at friends’ houses in the winter which he’d spend developing or printing from the many rolls of films taken that year. He said that he didn’t want to take pictures of people who were worse off than him, although his aim was too low: the gypsies at least lived in caravans and had television and heating whereas he slept outside every night and had one pair of trousers for the whole year. In the exhibition we see for the first time self-portraits of Koudelka asleep on office floors or outside the ground in the open air, sometimes a city skyline or a stand of trees in the distance behind him.

That is the romantic image, the vagabond artist creating effortlessly great art. But in reality the amount of work required was staggering. Each year Koudelka would shoot more than a thousand rolls of film. Over a twenty year period, that amounted to more than 300,000 images — and from that, only around a hundred pictures found their way to Exiles. Most years would only result in a few images. Photography is ultimately a work of selection, and Koudelka was merciless in selecting images from his own work. On the contact sheets, images were graded into categories, with only the ultimate, highest category leading to possible inclusion in a book. One must learn to be a good critic, and in fact I learned that Koudelka was the only photographer at Magnum who responded to Cartier-Bresson’s request for criticism.

Koudelka is the last, and his work has not been exhibited in any significant way Paris for many years. I hope that one day before too long we will have a retrospective of his work. Recently, Koudelka has returned to the panoramic images which have fascinated him since his early days in Prague; these images would certainly benefit from gallery space. But today, it is wonderful to see these photographs from Exiles on the walls of Beaubourg, and I will try to return again before the end of May.