Making things and finding out about things

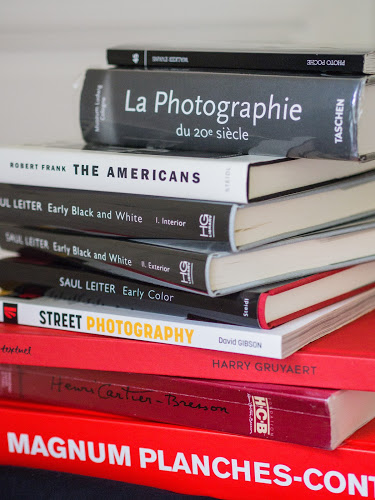

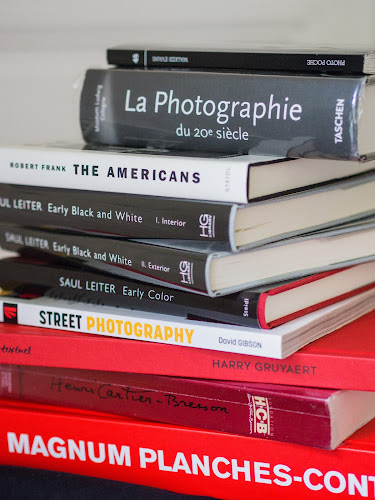

The last few months I’ve devoted a lot of my energies, outside of work, to photography. That is probably why the number of blog posts have declined. I spend a lot of time looking when I am out walking around Paris, and I spend a fair amount of time back here in the apartment looking at these images I have captured. I bought a fair amount of photography books too – there is a big pile of them here in the living room, and I don’t know what to do with them all. Our shelves are already full and our Parisian apartment is, as you can imagine, not too large. There is: The Magnum contact prints (an enormous book), the retrospective on Henri Cartier Bresson from the Bibliotheque Nationale around ten years ago (which seemed a better book to me that the one from recent retrospective at Beabourg, although I can’t comment on the shows as I missed them both), Robert Frank’s The Americans, three Saul Leiter books (Recent Color and the two books about his black and white photographs), a book of the recent Harry Gruyaert expo at the Musee Europeén de la photographie, a small book about Walker Evans, and a Taschen History of Photography of the 20th century. All these books I bought in the last twelve months! What is so interesting about these texts is that they all show the different ways there are of seeing the world. I do have to write something about these photographers, at least about Gruyaert, who is less discussed on the internet than the others. These books are inspirational. It is certainly easier to find great images here than trudging through Flickr (although there are some great images in there, you just need to know where to look)

But of course there is also the act of taking photographs itself. Now, as I said last summer, I have been taking photographs with digital cameras at least since 2003, and with analogue cameras before that (although not so often it has to be admitted). But I think I really didn’t think, or didn’t think too hard about what the photograph I was taking actually was, until last summer – they were snapshots. That at least has changed, I am thinking more. I am consciously trying to select individual photographs to put on Flickr, after some mucking around in Lightroom (I am not saying Flickr is the best place to put photographs, but the act of making them publicly visible makes you think more.) Being criticial, I don’t think that I am yet able to really do colour photography, or at least I am going back to looking at most things in black and white. The wonderful thing is that in all these photographs, there are one or two good photographs. That creates a special feeling – to have created some object, some thing, which didn’t exist before. I have to say, through photography, I never really felt that way before. It is the same feeling when you write a text. You made something exist which didn’t exist before, and as well as that, sometimes, it is something which you don’t feel terrible about having created (yes, I know). Yes, artists writers and painters must know all about this. But remember I am a scientist. And you know the funny thing? It seems to me that the act of creation alone isn’t enough. There is also stuff to be found out. There is knowledge to be gained. At the same time, science without creation seems to me to be sterile. A lot of the science that we have to do these days seems to be like that. Gone, of course, are the days when one great idea or one fantastic thought could change things. We are very much in the process of the incremental addition of knowledge (which I admit even Newton noticed). Because so much knowledge already exists, and because our picture of the Universe is already so detailed, it requires very extensive hardware and careful planning to make significant advances. Work takes place in vast highly-rational systems which punish deviation, and so they should because otherwise the work will not get done. What the crazy people who write letters to astronomers don’t realise is that not only should their theory explain (say) Dark Matter (a favourite) but it must also explain all the previous observations made up until then. That is a tall order, and that requires all those sattellites and telescopes and computers — which incidentally we get almost for free. They are the byproducts of our civilisation which is driven by other imperatives than the pure search for knowledge. What is the conclusion? Well, one is easier than the other; there is a place for both; and science is hard.